|

The Duke of Abruzzi

Luigi

Amedeo di Savoy, Duke of Abruzzi [1873 - 1933]

was born in Madrid to the then king of Spain also a

Savoy, who abdicated his throne only a few weeks after

his son's birth and returned to Italy. When he was six

years old, young Luigi was assigned to the Italian Navy

and received his entire education in military schools.

A man of great energy and imagination, at the age of

24 he organised and led the expedition that made the

first ascent of Mount St Elias [5,484 metres] in Alaska

in 1897. Luigi

Amedeo di Savoy, Duke of Abruzzi [1873 - 1933]

was born in Madrid to the then king of Spain also a

Savoy, who abdicated his throne only a few weeks after

his son's birth and returned to Italy. When he was six

years old, young Luigi was assigned to the Italian Navy

and received his entire education in military schools.

A man of great energy and imagination, at the age of

24 he organised and led the expedition that made the

first ascent of Mount St Elias [5,484 metres] in Alaska

in 1897.

Two years later he led an expedition to the North Pole

which reached a latitude 86^34' north, a new record

at the time. In 1906 he led the Rwenzori expedition

which climbed all the major peaks and made the most

extensive exploration of the range before or since.

A few years later, in 1909, he organised an expedition

to the Karakoram and set the record to the highest altitude

yet achieved by ascending the second highest mountain

in the world, K2, to a height of about 7,500 metres

[24,600 feet], along the route that today bears his

name, the Abruzzi ridge. On the same journey he increased

this record when he ascended Chogolisa (Bride Peak)

to an even higher altitude, 7.654 metres (about 25.110

feet), but did not reach the summit.

The first ascent to the summit of Chogolisa was not

made until 45 years later. During his great period of

adventure and exploration, the Duke of Abruzzi remained

a professional naval officer and on 30 September 1911

he commanded the squadron that attacked Preveza, Greece,

in the first action of the Italian – Turkish War.

Later, he commanded the Adriatic fleet of the Italian

navy in World War I and is warmly remembered in Italy

for his heroic rescue of more than 100.000 Yogoslav

refugees from Albania. In his last years he became interested

in the exploration and agricultural development of Somalia

and Ethiopia, eventually marrying a Somali wife. After

several expeditions to the region and the establishment

of various agricultural schemes, he died in Ethiopia

on 18th March 1933, where he was buried. In the 1980th

the Duke’s family hoped to have his remains exhumed

and returned to Italy, but bowed to the wishes of the

Ethiopian villagers who refused to allow the exhumation,

wanting to keep his remains – and memory –

with them.

From

“Uganda Rwenzori –

A range of Images”, by David Pluth, 1996

Little Wolf Press, Switzerland.

Luigi Amedeo Duke

of Abruzzi was the third born of Amedeo

(1845-1890), first Duke of Aosta and king of Spain from

1870 to 1873. He does not have direct heirs, but the

Aosta line is today represented by the fifth Duke of

Aosta, Amedeo, born in 1943. Amedeo

has already visited Uganda on the occasion of the 90th

celebrations that took place in 1996 and he shall be

once again in Uganda on the occasion of the Centenary.

Luigi Amedeo of Savoy , duke of Abruzzi together

with A.F

Knowles at the feet of the Rwenzori in 1906.

THE DUKE OF ABRUZZI

AND AFRICA

By Mirella Tanderini

Until the First World

War, the Duke of Abruzzi enjoyed an enormous popularity,

both in Italy and abroad for his success in expeditions.

After the war the duke retired from the navy and all

his efforts aimed at building a farming colony in Somalia

with the co-operation of Somali people. It was a dream

he had nourished for a long time, since he first set

his foot on the African coast in 1883 and fell in love

with the Continent.

He succeeded in raising funds to reclaim land, build

dams, roads and a railroad, factories and houses, schools,

a fully equipped hospital, a Catholic church and a Mosque

for 3.000 people living and working in the village that

was called after his name.

His last expedition, in 1928, was to locate the sources

of Uebi-Scebeli, the river on which his village was

built, and to map the whole region down from Ethiopia

highlands to the coastal Somalia. He spent his last

days in his village and he wanted to be buried there,

in the Continent he loved. His experiment of co-operation

between European capital and technologies and African

resources and labour was scarcely understood at this

time, but the company he had set up went on successfully

also after his death. When Somalia became independent

it was nationalised and until 1992, when it was ravaged

by civil was, it continued to be the major producer

of sugar in the country.

After the Second World War, Italy became a Republic

and that perhaps was one of the reasons why the Duke

of Abruzzi was forgotten by his own fellow country men.

Luigi Amedeo, Duke of Abruzzi was a Prince of the Crown

and a cousin of the King Vittorio Emanuel III of Savoy

that had allowed Fascism to rule Italy and to ally with

the Nazi regime of Germany, and although he personally

never approved of Mussolini and kept away from politics,

the citizens of the new Republic preferred to forget

about all the Savoys and for fifty years the Duke of

the Abruzzi was scarcely mentioned in encyclopaedias

and books on exploration and mountaineering.

After the Second World War, Italy became a Republic

and that perhaps was one of the reasons why the Duke

of Abruzzi was forgotten by his own fellow country men.

Luigi Amedeo, Duke of Abruzzi was a Prince of the Crown

and a cousin of the King Vittorio Emanuel III of Savoy

that had allowed Fascism to rule Italy and to ally with

the Nazi regime of Germany, and although he personally

never approved of Mussolini and kept away from politics,

the citizens of the new Republic preferred to forget

about all the Savoys and for fifty years the Duke of

the Abruzzi was scarcely mentioned in encyclopaedias

and books on exploration and mountaineering.

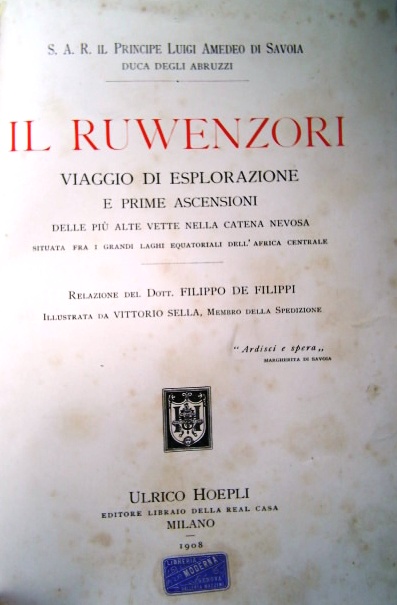

It is the merit of the Kampala Conference (April 1996)

to have anticipated a revival of interest for the Duke

of Abruzzi on the occasion of the 90th anniversary of

the Rwenzori expedition. There is a wealth of documentary

material surviving: the accounts of the Duke’s

expeditions, the book of Filippo de Filippi containing

the extraordinary photos of Vittorio Sella (he was developing

the photos in a tent working as dark room while up on

the mountains), the maps and all the documents kept

by the Fondazione Sella at Biella and in the Museum

“Duca degli Abruzzi” in Turin and in the

archives of foundations, alpine clubs and geographic

societies all over the world. The Canadian writer Michael

Shandrick and myself wrote a book on the life of the

Duke. The ascent and the exploration of the Rwenzori

massif is one of the most fascinating chapter in the

book and we, the authors, are pleased that the celebrations

for the Duke of Abruzzi started in the Continent that

was the country of his choice in a period of history

when Europeans considered it as a territory to conquer

and exploit. It is a most significant event and the

starting point of new studies and conferences that will

render justice to a great explorer who was neglected

for too long.

The above article was written by the Italian

historian Mirella Tanderini on the occasion of the celebrations

of the 90th anniversary of the Duke’s expedition

organized by the Department of Geography of Makerere

University, 1996.

|