|

History of the Climbing

before 1906

It was necessary

to wait until 1888 before having certain information

about the existence of the Mountains of the Moon. On

May 24th of that year, the famous English journalist-explorer,

Henry Stanley, finally succeeds in glimpsing

the snow-capped peaks of the Rwenzori, as he travels

along the coastal plain southwest of Lake Albert.

As a matter of fact Stanley is not the first person

to sight the great snow-covered mountains, which are

shortly to be known as the Rwenzori. During the preceding

years, in different circumstances and periods, Samuel

Baker and Romolo Gessi had succeeded in catching a glimpse

of great mountainous masses away in the distance, to

the south of Lake Albert.

However the fogs and mists from the low lands obscured

and confused their form and profiles to the point of

transforming them into a vision of something unreal,

similar to a hallucination or mirage. As far as he is

concerned, Stanley is absolutely certain that the great

mountains on the horizon are Ptolemy's Lunae Montes.

Indeed, of all the peaks scattered round the middle

of equatorial Africa, only the ice-capped summits of

the Rwenzori correspond to the ancient's descriptions.

Lake Kitandara by Vittorio Sella

In any case, his discovery throws new light on the geography

of the region. Not only: it also confirms, quite remarkably,

the tenacious tradition which sees the Nile rising from

the Great Lakes fed by snow-covered mountains. In a

word the image dear to Aeschylus of an "Egypt nourished

by snows", returns to being an extraordinary relevance

to the present day. Henry Stanley is once again in the

Rwenzori area the following year, 1899, and travels

along the Western flank of the mountainous group.

Between spring and summer he remains for a long time

in the vicinity the range, and from time to time succeeds

in catching sight of some the higher snow-capped peaks.

Eager to get on closer terms with the mountains of the

moon, he instructs is deputy W.G. Stairs to

carry out a short explorative trip to the heart of the

imposing relief. From Bakokoro camp Stairs ascends one

of the valley to the North-West of the range for two

days, aiming towards two characteristic rocky peaks.

He advances to altitudes 3254, about 500 meters below

the two peaks and from up there he manages to observe

a snow-capped summit which he believes to be higher

than 5000 meters and which, however, does not seem to

be the highest of the group. Ill-equipped for a long

stay at high altitude, Stanley's deputy quickly retraces

his steeps, returning with the idea that the Rwenzori

group is of volcanic origin. He is wrong. In the following

years other attempts at exploration are registered.

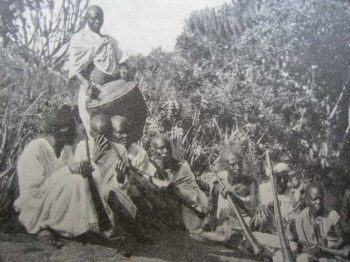

Baganda Musicians photo by Vittorio Sella

In June 1891 F. Stuhlmann, following

on Emin Pasha's expedition, ventures for five days into

the upper Butagu valley, one of the most important on

the western side of the range. He reaches 4036 meters,

in the sight of two snow-capped peaks, and is then obliged

to turn back. On his return he relates the succession

of the various phases of vegetation with an abundance

of details, but above all he describes the Rwenzori

as a real mountain range, composed of four principal

groups, and certainly not of volcanic origin.

A new explorative impetus in the area takes place in

the years 1894 to 1895, carried out by the naturalist

G.F. Elliot who makes five reconnaissance

trips in the five different valleys (the first four-

Yeria, Wimi, Mobuku and Nyamwamba-on the eastern slope,

and the last - Butagu- on the western one). He reaches

a maximum of 3962 meters in the Butagu valley but he

is able to gather any data about the high altitude regions.

Instead, his geological observations on the signs of

old glaciations in the area are very useful. Then, for

five long years the Rwenzori continues to drowse undisturbed.

Social tensions and problems within the British Colony

in Uganda steer interest for the mountains elsewhere.

Exploration of the great African relief starts up again

in the spring of 1900 with C.S. Moore, head of a scientific

expedition working in the area of the Great Lakes. With

a few Swahili explorers and some indigenous people Moore

ascends the whole Mobuku valley reaching right up to

the terminal crest, at altitude 4541.

During his visit to the Rwenzori, the British explorer

succeeds in demonstrating the presence of true glaciers

(and not the simple snowy accumulations as had been

thought up to that moment). Few weeks later another

two excursions at high altitude are registered: the

first by Ferguson, a member of Moore's expedition; the

other by a certain Bagge, a civil servant from the mining

district of Toro.

Finally, in September, Sir Harry Johnston,

a high commissioner of the English colony in Uganda,

with two companions ascends the Mobuku Valley right

up to altitude 4520, without however managing to reach

the crest.

The high commissioner also succeeds in taking some good

photographs of the valley and in compiling an accurate

description of the mountain vegetation and fauna. An

important detail: Sir Johnston, just like his predecessors,

cannot but mention the constant appalling weather, which

scourges the area.

A continual stream of visitors, all convinced of being

able to throw light on the topography of Rwenzori, appear

during the immediately successive years. In August 1901,

W. H Wylde and Ward climb to the same

altitude reached previously by Moore. Two years later,

Reverend A. B. Fisher and his wife

go as far as the point that Sir Johnston reached. Then,

in 1904, the newspaper Globus carries news of another

climb. A short report states that J. J David had reached

an altitude of 5000.

The first, real, mountaineering attempt of the Rwenzori

belongs to a year later, November 1905. William

Douglas Freshfield and Arnold Louis

Mumm arrived at the Mobuku Valley together

with the Alpine guide Moritz Inderbinnen from Zermatt.

Ferment around the Rwenzori continues to increase. Only

a month earlier, in October, a scientific expedition

from the British Museum left London, led by A.B. Woosnam.

G. Legge, R.E. Dent, M. Carruthers and the mountaineer

A.F.R. Wollaston make up part of the

group.

And that is not all. In January 1906 Reverend Fisher

and his wife return for a second time to the Mobuku

glacier. And an Austrian mountaineer, R. Grauer,

together with two British missionaries, H.E Maddox and

H.W. Tegart, who had already been on the glacier the

preceding yera, reach the crest which closes the valley,

not climbed since 1901, and scale a rocky pinnacle,

the King Edward Peak.

Meanwhile the English expedition reaches Mobuku Valley.

First Woosnam, and then a small group of explorers made

up of Wollaston, Dent and fhe same Woosnam, climb to

the point already reached by Grauer. Afterwards, Woosnam

and Wollaston attempt to climb Kiyanja [Stuhlmann's

Seper,today Mount Baker]. Because of the fog they have

to stop below the summit at an altitude estimated at

4915 metres.

Then, on April 1st, Woosnam, Wollaston and Carruthers

reach a peak 4844 metres high which dominates the valley

to the north-east; they think it is Johnston's Duwoni.

At the end, three days later, the roped party returns

to the rocky pinnacle of Kiyanja, which, on a second

measuring results higher: 4992 metres.

After Stuhlmann's observations, it is common belief

that the Ruwenzori are made up of four main mountain

groups; nevertheless it is not known if these are if

these are connected to each other or separated by valleys

or valley systems. Besides, the altitude of the main

peaks is subject to divese hypotheses, which go from

5000 to over 6000 metres; but, who knows, there could

be even higher peaks still to be discovered.

From “The

Rwenzori Discovery- Luigi Amedeo di Savoia Duca degli

Abruzzi”, by Roberto Mantovani, Museo Della

Montagna 1996.

|